This is the story of a gigantic (so to speak) scholarly “oopsie”-

In late 1915 Gisela Richter, renowned expert on Greek and Roman antiquities at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, received a letter from John Marshall, the Museum’s veteran purchasing agent in Italy, describing a newly discovered life-size Etruscan warrior figure in terra-cotta which had been discovered in an Italian field.

The “old warrior” (he had a white beard and was emaciated, somewhat like, as one observer commented later, a Giacommetti sculpture) was soon followed by a massive four-foot tall terra cotta warrior’s head, and there was even talk of a greater treasure waiting to be found...

It was, of course, all fakery, carried out on a grand, almost “mythic” scale, a scale meant to make experts put aside all their nagging doubts and see the “Etruscans” as what they were not (namely, ancient). The white-bearded warrior and the massive head had been created by Riccardo Riccardi and Alfredo Fioravanti, two young men of skill and a certain vision. Riccardo’s father and brothers had also specialized in historic pottery, but Riccardo was the true genius of the family. With his friend Alfredo he first created the anorexic, white-bearded warrior.

The figure was modeled as one piece and then broken up into 24 fragments for firing, as the kiln was not large enough to accomodate the entire figure. The warrior is missing his right arm for the simple reason that the two forgers could not agree on how to position the arm, so they compromised by breaking it off and discarding it.

After selling the figure to the Metropolitan, the pair began work on another figure, this time a gigantic warrior's head. Working from a description by Pliny of a 25-foot tall statue of Jupiter in a Roman temple, the pair made the head four and a half feet tall. This was broken into 178 pieces, fired, and shipped off to the Met. And then Riccardo and Alfredo had to leave to serve their time in the Italian Army.

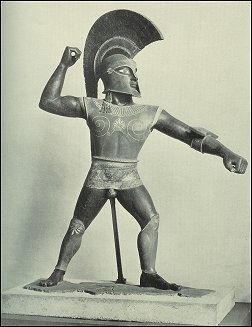

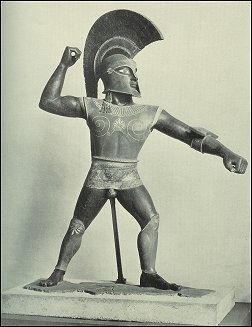

When they returned they began their most audacious project yet- a Colossal Warrior in terra cotta, standing over eight feet tall. Then tragedy struck. Riccardo was killed in a fall from his horse that winter, and his place was taken by two less-skilled cousins. As with the earlier pieces, the statue had to be fired in pieces as it was much too large for the kiln.

It proved, in fact, to even be too large for the room it was being modeled in, and by the time they had modeled up as far as the waist it was obvious that the elegant classical proportions of genuine Etruscan sculpture would have to be ignored -there simply was not enough room for the upper body without going through the ceiling. The odd result- classical legs and a stocky, disproportionate torso, troubled some scholars.

In 1921 the Met. purchased the warrior for an undisclosed price said to have approached 5 million dollars in today’s money. The statue was reconstructed from the fragments by the Met's experts with one odd exception- the genitals, which had been carefully modeled (the warrior, like many Etruscan statues, was partially nude from the waist down) were left off and apparently kept in storage. It may have been just as well. One story that came to light later related that while the body of the figure was based upon that of Riccardo's cousin and helper Teodoro, the "privates" were modeled after Riccardo's own, and had been recognized by a number of young Italian ladies of his hometown...

Attempts to erase doubts that were already being whispered in art circles in Europe, as well as the hope that the “secret” field they had been found in might be divulged by their “discoverers”, delayed the publication of a scholarly monograph on the three figures until 1937. For Richter, bringing them to the Met. and publishing them represented one of the crowning achievements of her distinguished career, and it was undoubtedly this fact that blinded her to what was becoming all too obvious to other scholars who were not emotionally or professionally attached to the warriors.

The talk about their true origins swirled quietly for the next decade or two, but after a visiting Italian scholar was offered a chance to see all three statues in 1959, and commented that he did not need to see them since he knew the man who had made them, authorities at the museum decided something had to be done. In 1960 a series of tests concluded that the glazes on all three specimens contained chemicals which had not been in use before the 17th century, and in 1961 Fioravanti signed a confession of the whole affair, and supplied a missing thumb which fit perfectly.

At that point several other “bothersome” points that had been noted over the years began to make more sense- the Colossal Warrior, for instance, could not even support its own weight, and when compared to real Etruscan statuary, simply looks crude and even modern. Today the statues are stored far away from prying eyes, but they still provide an entertaining and sobering lesson in fake busting.

A much more detailed account of the warriors was written by David Sox in his excellent book “Unmasking the Forger, The Dossena Deception” (1987), from which most of the material for this essay was taken; Thomas Hoving, the former Director of the Met., also deals with the story, and speculates on the role of John Marshall, in his book "False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes" (1996).

This is the story of a gigantic (so to speak) scholarly “oopsie”-

This is the story of a gigantic (so to speak) scholarly “oopsie”- The “old warrior” (he had a white beard and was emaciated, somewhat like, as one observer commented later, a Giacommetti sculpture) was soon followed by a massive four-foot tall terra cotta warrior’s head, and there was even talk of a greater treasure waiting to be found...

The “old warrior” (he had a white beard and was emaciated, somewhat like, as one observer commented later, a Giacommetti sculpture) was soon followed by a massive four-foot tall terra cotta warrior’s head, and there was even talk of a greater treasure waiting to be found... After selling the figure to the Metropolitan, the pair began work on another figure, this time a gigantic warrior's head. Working from a description by Pliny of a 25-foot tall statue of Jupiter in a Roman temple, the pair made the head four and a half feet tall. This was broken into 178 pieces, fired, and shipped off to the Met. And then Riccardo and Alfredo had to leave to serve their time in the Italian Army.

After selling the figure to the Metropolitan, the pair began work on another figure, this time a gigantic warrior's head. Working from a description by Pliny of a 25-foot tall statue of Jupiter in a Roman temple, the pair made the head four and a half feet tall. This was broken into 178 pieces, fired, and shipped off to the Met. And then Riccardo and Alfredo had to leave to serve their time in the Italian Army. In 1921 the Met. purchased the warrior for an undisclosed price said to have approached 5 million dollars in today’s money. The statue was reconstructed from the fragments by the Met's experts with one odd exception- the genitals, which had been carefully modeled (the warrior, like many Etruscan statues, was partially nude from the waist down) were left off and apparently kept in storage. It may have been just as well. One story that came to light later related that while the body of the figure was based upon that of Riccardo's cousin and helper Teodoro, the "privates" were modeled after Riccardo's own, and had been recognized by a number of young Italian ladies of his hometown...

In 1921 the Met. purchased the warrior for an undisclosed price said to have approached 5 million dollars in today’s money. The statue was reconstructed from the fragments by the Met's experts with one odd exception- the genitals, which had been carefully modeled (the warrior, like many Etruscan statues, was partially nude from the waist down) were left off and apparently kept in storage. It may have been just as well. One story that came to light later related that while the body of the figure was based upon that of Riccardo's cousin and helper Teodoro, the "privates" were modeled after Riccardo's own, and had been recognized by a number of young Italian ladies of his hometown... A much more detailed account of the warriors was written by David Sox in his excellent book “Unmasking the Forger, The Dossena Deception” (1987), from which most of the material for this essay was taken; Thomas Hoving, the former Director of the Met., also deals with the story, and speculates on the role of John Marshall, in his book "False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes" (1996).

A much more detailed account of the warriors was written by David Sox in his excellent book “Unmasking the Forger, The Dossena Deception” (1987), from which most of the material for this essay was taken; Thomas Hoving, the former Director of the Met., also deals with the story, and speculates on the role of John Marshall, in his book "False Impressions: The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes" (1996).

The Book Elves have a tradition of being hard on pots and plates- there was the time they decided to "Class Up" the greenhouse by repotting all the cacti in the 18th century Sevres; there was that regrettable incident after too much eggnog last Christmas when they tried to find out how high "too high" was when it came to stacking the Wegdwood dinnerware; and we're all trying to forget last July 4th's infamous "Great Minton Shoot"...

The Book Elves have a tradition of being hard on pots and plates- there was the time they decided to "Class Up" the greenhouse by repotting all the cacti in the 18th century Sevres; there was that regrettable incident after too much eggnog last Christmas when they tried to find out how high "too high" was when it came to stacking the Wegdwood dinnerware; and we're all trying to forget last July 4th's infamous "Great Minton Shoot"... It was an odd January here at Foggygates- lots of cold, but no snow. That, however, was not going to stop the Book Elves from enjoying themselves, so after a hard day in the Cataloging Cave they planned to hit the “slopes” in the neighbor’s field, making snow with the help of two garden hoses, 300 feet of heavy duty extension cord and a dozen old industrial fans they picked up cheap at a local farm auction.

It was an odd January here at Foggygates- lots of cold, but no snow. That, however, was not going to stop the Book Elves from enjoying themselves, so after a hard day in the Cataloging Cave they planned to hit the “slopes” in the neighbor’s field, making snow with the help of two garden hoses, 300 feet of heavy duty extension cord and a dozen old industrial fans they picked up cheap at a local farm auction.